SPOILER ALERT: Things you might want to know before suggesting this to your kid

Family

Madison’s real life parents are barely characters, so their behavior might go over the heads of most readers. Still, they are both absent parents, and sort of unaware of Madison’s issues even when they’re home. It’s only when Grandma sits everyone down for an intervention that her parents wake up and promise to be more involved.

Violence & Death

No one dies in the story, but the idea of death is a threatening one that hangs over several characters. The disappearance of the “men” frightens the dolls, and Madison’s callousness about the event is creepy, even if it serves to prove a point about her troubled life.

Protagonist/Antagonist

One interesting bit of the book is that Madison goes from being the scary Big Bad in the dolls’ lives to being the lonely protagonist in her own life. That’s a big switch, and it might jar some readers, mostly because it happens very fast in the last part of the book.

Story

The entire movie runs in flashback which sets the major characters in place. Rustin, a drug addict who abandoned his wife and daughter and moved to the Philippines, comes back to Rotterdam after eight years to make repairs and meet his daughter.

His wife had died and so Yumi, Rustin’s daughter, lived with her aunt Rachelle and uncle Bok. Rustin comes into their lives as Clyde to gatekeep his real identity.

However, his efforts all go in vain when Rachelle recognizes him over a video chat. Even though he is forbidden from visiting Yumi, he tries to find ways to keep meeting her. Yumi and Rustin share a deep bond until the end.

Rustin’s addiction to drugs and alcohol creates quite a few hurdles in the movie. He sails all through the tempest until one day he falls sick and then unconscious due to an overdose.

Years later, when Yumi gets to know that Rustin was her biological father, she goes to visit him in a healthcare centre where he resided after suffering a stroke.

The stroke had affected his memory and he could not recognize Yumi when she visited him. However, he kept his promise that he had made to little Yumi and finished the dollhouse he was to give to her before he was hospitalized due to an overdose.

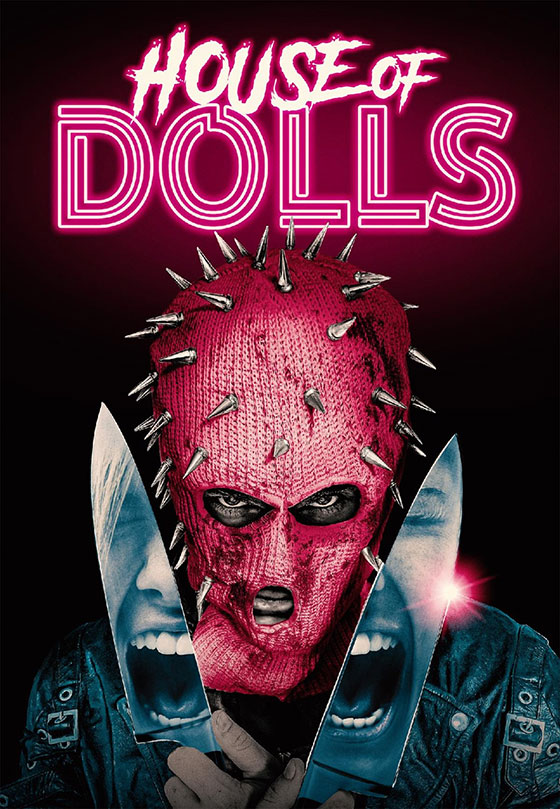

‘House of Dolls’ VOD Review

by Jim Morazzini

Stars: Alicia Underwood, Taylor Cox, Naomi Lopez, Jack Rain, Dee Wallace, Meeko | Written by Juan Salas, Iv Amenti | Directed by Juan Salas

House of Dolls refers to the house where three estranged, to put it mildly, sisters Diana (Alicia Underwood; Ghost Note, When Androids Dream), Helen (Taylor Cox) and Charlotte (Naomi Lopez; New Year’s Evil, The Devil’s Ring) are forced to deal with each other in order to collect an inheritance.

Considering how much they hate each other there must be a lot of money at stake to make the three of them plus Charlott’s boyfriend Justin (Jack Rain; AWOL-72, Desecrated) spend a weekend in a house built to resemble a giant dollhouse. But, according to their grandmother Celine (Dee Wallace; Critters, The Nest) his final wish was that they reconcile so here they are.

Large sums of money might also explain the masked killer who’s roaming Los Angeles killing anyone with a connection to the girls. That ranges from one of their boyfriends to the manager of the club where aspiring musician Charlotte’s video shoot was interrupted by a police bust.

I have a feeling director Juan Salas (The Wolf Catcher, The Trple D) found this location and then he and co-writer Iv Amenti quickly whipped up House of Dolls’ script to shoot in it. And I say quickly because it doesn’t feel like any time or effort was put into giving the viewer anyone to care about, or anything resembling a coherent plot.

Most of the first act is our introduction to the three sisters and it does a good job of letting us know just what unlikable people they are, especially the coked-out diva Charlotte. And if they’re annoying separately you can imagine what they’re like once they’re brought together to hunt for the clues he left to the money’s whereabouts.

Most viewers will be more interested in the trail of bodies that the House of Dolls’ killer is leaving in his wake. They are bloody and include a disembowelment, a smashed-in skull and somebody crucified against a refrigerator and then cut in half with a chainsaw. There’s an almost giallo-like level of sadism and violence on display here and it’s done with practical effects.

Unfortunately, while the killer’s leather trenchcoat looks menacing enough their pink spiked ski mask just looks silly. The scene where they headbutt someone to death with it looks funny rather than frightening as are multiple scenes where characters just walk up to the killer yelling at them until they get stabbed. Worst of all, in one of the film’s more important scenes the victim suddenly acquires a very noticeable shower cap when they’re knocked into the pool.

To that we can add some predictable plot devices, a cop (Meeko; Night Rapper, The Monster) who is one step behind the killer, one of the sisters being killed and the remaining two decide not to call the cops but keep hunting for the cash, the silent killer who gets chatty in the last few minutes and his very predictable identity. And, of course, lots of crappy music on the soundtrack.

Now to be fair, House of Dolls does have some nicely lit and composed shots courtesy of cinematographer Jorge Villa (The Devil’s Ring, Mr Lee: 20 Years of Power) including part of a murder scene reflected in a piece of a shattered mirror. They further suggest that Salas was aiming at creating a giallo and fell short of the mark.

Some good kills and the occasional flashes of potential stop House of Dolls from being bottom of the barrel, but they can’t do much to offset an extremely weak script and some equally poor acting.

Product details

- ASIN

:

B072TVPN1N - Publisher

:

HQ Digital (14 Sept. 2017) - Language

:

English - File size

:

4467 KB - Text-to-Speech

:

Enabled - Screen Reader

:

Supported - Enhanced typesetting

:

Enabled - X-Ray

:

Enabled - Word Wise

:

Enabled - Sticky notes

:

On Kindle Scribe - Print length

:

418 pages

- Best Sellers Rank: 54,439 in Kindle Store (See Top 100 in Kindle Store)

- 454 in Action & Adventure Literary Fiction

- 472 in Women’s Adventure Fiction (Kindle Store)

- 497 in Psychological Literary Fiction

Customer reviews:

/*

* Fix for UDP-1061. Average customer reviews has a small extra line on hover

* https://omni-grok.amazon.com/xref/src/appgroup/websiteTemplates/retail/SoftlinesDetailPageAssets/udp-intl-lock/src/legacy.css?indexName=WebsiteTemplates#40

*/

.noUnderline a:hover {

text-decoration: none;

}

.cm-cr-review-stars-spacing-big {

margin-top: 1px;

}

4.2 out of 5 stars

5,095

var dpAcrHasRegisteredArcLinkClickAction;

P.when(‘A’, ‘ready’).execute(function(A) {

if (dpAcrHasRegisteredArcLinkClickAction !== true) {

dpAcrHasRegisteredArcLinkClickAction = true;

A.declarative(

‘acrLink-click-metrics’, ‘click’,

{ «allowLinkDefault»: true },

function (event) {

if (window.ue) {

ue.count(«acrLinkClickCount», (ue.count(«acrLinkClickCount») || 0) + 1);

}

}

);

}

});

P.when(‘A’, ‘cf’).execute(function(A) {

A.declarative(‘acrStarsLink-click-metrics’, ‘click’, { «allowLinkDefault» : true }, function(event){

if(window.ue) {

ue.count(«acrStarsLinkWithPopoverClickCount», (ue.count(«acrStarsLinkWithPopoverClickCount») || 0) + 1);

}

});

});

Origins[]

The origin of Ka-tzetnik’s story is not clear. Some say it is based on a diary kept by a young Jewish girl who was captured in Poland when she was fourteen years old and forced into sexual slavery in a Nazi labour camp. However, the diary itself has not been located or verified to exist. Others claim, and the author suggests as much in his later book Shivitti, that it is based on the actual history of Ka-tzetnik’s younger sister (House of Dolls is about the sister of Ka-tzetnik’s protagonist, Harry Preleshnik).

Between 1942 and 1945, Auschwitz and nine other Nazi concentration camps contained camp brothels (Freudenabteilung «Joy Division»), mainly used to reward cooperative non-Jewish inmates. Not only prostitutes were forced to work there.

In the documentary film, Memory of the Camps, a project supervised by the British Ministry of Information and the American Office of War Information during the summer of 1945, camera crews filmed women who had been forced into sexual slavery for the use of guards and favored prisoners. The film makers stated that as the women died they were replaced by women from the concentration camp Ravensbrück.

The book Stella: One Woman’s True Tale of Evil, Betrayal, and Survival in Hitler’s Germany, a biography of Stella Goldschlag, says she was threatened with being forced into sexual slavery unless she cooperated with the Nazis.

Why A Doll’s House is Still Relevant Today

Henrik Ibsen’s play A Doll’s House may be 140 years old but this story of a failed marriage still commands our attention. According to the Center for Ibsen Studies in Oslo, it’s the second most-produced play in the world after Hamlet. A recent sequel play, Doll’s House Part Two, is now playing in regional theaters across the country, many of which are also staging revivals of Ibsen’s play, and several adaptations of A Doll’s House are currently in theaters around the world. What explains the power of this story? I’ve spent the last decade writing my own sequel to A Doll’s House, a novel set in Ibsen’s Norway and 1880s America, and I can tell you this: Ibsen’s play resonates for audiences today because many modern women face the very same questions Nora confronted, questions of love, self-determination and family. Yes, we have more rights and opportunity than Nora, but we often grapple with the same difficult choices that Ibsen throws at Nora’s feet.A Doll’s House is about the breakup of two people who thought they were in love. For modern society, the specter of divorce looms large, even for couples that stay together. Their friends divorce, their aging parents divorce – it seems like it can happen to anyone. Even the best marriages struggle between idealized perceptions and stark reality—one of Ibsen’s favorite themes. As we watch his play unfold, we recognize the Helmers’ games and vanities, as well as the corrosive power their individual secrets. And yet, like us, the Helmers are fairly normal people – admired by their neighbors, trying to do their best but stumbling over the vicissitudes of life. They are not evil or bad; they just want different things. In significant ways, we are all the Helmers. We also understand Nora’s longing to be more than just a wife, her hunger to choose her own life instead of fitting into her husband’s. Women in oppressive partnerships often find ways of to develop their own agency, and when Nora breaks the law to save her husband’s life (against his wishes), we get it. And when she doesn’t get credit, and is treated as a criminal instead of a hero, we get that, too. Self-determination can be a minefield; most modern women know that and recognize Nora’s efforts as kindred to their own. And when Nora must leave her children behind as she walks away from her marriage, we understand that as well, even as our hearts break. Those of us who have divorced often lose time with our children; that’s just a reality of gender-neutral custody law. In Nora’s day, she would have had no legal right to care for her children, and in some parts of the world that is still true for mothers. Nora must leave her children because her lifeboat is only big enough for her. In the end, she chooses her own survival over the needs of her children. Unfortunately, there are still many women among us who face this difficult choice, especially those who fear they will not survive if they stay in a troubled or abusive marriage. I believe A Doll’s House still resonates with audiences for the simple reason that the revolution Ibsen started with Nora’s famous “slam heard ‘round the world” isn’t finished. In fact, there is much more work to do before all women are free to pursue their own self-determination while still caring for their children and getting a second chance at love. And we must recognize that all women today, despite our rights and opportunities, still stand on shifting ground. This is what Turkish writer Elif Shafak means when she says: “As societies slide backwards into authoritarianism, nationalism or religious fanaticism, women have much more to lose.” Go reread Ibsen’s famous play, or try my sequel novel Searching for Nora to see what Nora might have done with her independence. What Ibsen unleashed still echoes with potent themes. By Wendy Swallow, March 8, 2020 (International Women’s Day 2020)

The First Edition of A Doll’s House (Et Dukkehjem)

About Wendy Swallow

Wendy Swallow writes about women’s challenges, now and in the tender past. She is the author of Breaking Apart: A Memoir of Divorce and The Triumph of Love over Experience: A Memoir of Remarriage. Swallow became fascinated with Henrik Ibsen’s iconic character Nora Helmer after she left her first husband. Searching for Nora is her first historical novel.

- Nora and the Shadow of Prostitution — April 3, 2023

- National Novel Writing Month — November 5, 2021

- Five Surprising Things I Learned about Norway — May 5, 2021

- Laura Kieler: Ibsen’s Nora — January 9, 2021

- The Magic of Gift-Giving — December 3, 2020

- Nora and Solvi, the Movie — November 16, 2020

- Essay Questions — October 1, 2020

- The Weight of Creative Work — September 1, 2020

- Nora and the Shadow of Prostitution — July 11, 2020

- A Silver Medal for Searching for Nora — June 2, 2020

Literature and scholarly references[]

In his essay «Narrative Perspectives on Holocaust Literature», Leon Yudkin uses House of Dolls as one of his key examples of the ways in which authors have approached the Holocaust, using the work as an example of «diaries (testimonies) that look like novels» due to its reliance on its author’s own experiences.

Ronit Lentin discusses House of Dolls in her work Israel and the Daughters of the Shoah. In her book, Lentin interviews a child of Holocaust survivors who recalls House of Dolls as one of her first exposures to the Holocaust. Lentin notes that the «explicit, painful» story made a huge impact when published and states that «many children of holocaust survivors who write would agree . . . that House of Dolls represents violence and sexuality in a manner which borders on the pornographic».

Na’ama Shik, researching at Yad Vashem, the principal Jewish organisation for the remembrance of the victims of the Holocaust, considers the book as fiction. Nonetheless, it is part of the Israeli high school curriculum.

The success of the book showed there was a market for Nazi exploitation popular literature, known in Israel as Stalags. However Yechiel Szeintuch from the Hebrew University rejects links between the smutty Stalags and K. Tzetnik’s works which he insists were based on reality.

Performances

Baron Geisler executes the character of a troubled father exceptionally well. Traits of realism are sensed as Rustin’s character is raw.

At times, he is a caring father and at times, his present state – is one of addiction, distortion, and undisciplined. Such an amalgamation makes him stand out and proves to be worthy of the role of the protagonist.

Althea Ruedas who played the role of young Yumi was convincing and at times, heart-melting. Even though there was no character development, her acting did justice to the role.

Phi Palmos who embodied Bok’s character did well enough as a supporting actor. However, his involvement in the main plot seemed stretched and unnecessary.

The Doll House is available from Pink Eiga

There is a minimal plot, which is not surprising given that this runs for just over an hour, in which a doctor, Arthur, and his ‘recent’ wife, Yoko, move into a new home which is haunted by a murderous onryō, whose spirit it seems is hiding in a creepy Victoriana doll (although the relationship between the two is not terribly clear). Cue steamy sex scenes which are only interrupted by the appearance of the ghost, and not Arthur’s remarkable stamina, and a bloody ending. A subplot about an accident which ruined Arthur’s career as an elite doctor and his marriage to the Chief’s daughter doesn’t really go anywhere. We only know that he is unemployed because of it, which of course is useful because then he can have lots of sex without the day to day drudgery getting in the way.Given the tight budget and restricted shooting time that is an essential defining feature of pinku eiga – but without the political critique of the original cycle of films – Hashiguichi produces an entertaining and effective softcore horror film. Using a desaturated cinematic palate of green, browns and yellows for most of the film, and pillow or empty shots to heighten tension, “The Doll House” foregrounds Japanese cinematic eroticism without bringing the all too common misogyny with it. The emphasis is on Yoko’s desire as much as it is Arthur’s rather than codifying the conventions of male dominance in pinku eiga.

In addition, Hashiguichi doesn’t forget to utilize the generic features of J-horror including long dark hair clogging up bath water; the vengeful ghost appearing at the very edge of vision or as a reflection in the mirror; minimalist soundtrack and mainly still camera. In addition, repeated shots of the doll’s black sightless eyes watching the couple’s couplings add a suitably creepy feeling to the proceedings.

Significantly, only Yoko can see the ghost. And while she does attempt to enlist the help of the police in order to reveal the house’s bloody history, the ghost cannot be stopped from repeating the original trauma in which a mother killed and dismembered her daughter in the house. While Arthur might be the active instigator in terms of sex, he is the passive recipient of the ghost’s rage. The black beads that are the doll’s ‘eyes’ could be seen as a reference to the urban legend of the Okiku doll.

However, unlike the traditionally attired Okiku doll, the cursed doll here seems to be of Western origin or more appropriately interpreted as part of the Gothic Lolita trend and subculture which emerged in Japan in the late 1990s. In either case, the doll is, as always in horror films, darkly disturbing. Here her beaded eyes return the male gaze and foreground the disavowal of fragmentation that constitutes the male subject’s illusory agency and activity.

In conclusion, “The Doll House” is an effective example of the sex-horror film that has its genesis in 1960 political pinku eiga cinema and the subsequent mainstream studio film cycles including Nikkatsu’s roman porno. It has plenty of sex and enough moments of horror to satisfy fans of both genres.

Cast and characters[]

Main

Baron Geisler as Rustin Clyde Villanueva

- Rustin Clyde Villanueva (Baron Geisler) was the front man of a rock band. He and his bandmates led a hedonistic rock star lifestyle with alcohol and drugs. One night after a gig, his good friend Diego (Alwyn Uytingco) died at age 40. Suddenly shaken about his own mortality and his unfulfilled life, Rustin made the decision to backtrack on his past, and fly back to Rotterdam, where he has some unfinished business.. While walking along the familiar streets and landmarks, Rustin recalled about Sheena (Izah Hankammer), the wife whom he divorced years back. Outside a certain apartment, he met a gay Filipino man named Bok (Phi Palmos) and his cute niece Yumi (Althea Ruedas). He learned that Yumi’s mother passed away three years ago in a car accident, and her father was a worthless Filipino drug addict who abandoned his family. Baron Geisler may fit the role of an irresponsible, alcoholic, drug addict and rock singer to a T. But the rest of the film where Rustin (using his auxiliary name Clyde) playing and interacting with a spirited little kid Yumi is something we thought we’ll never see. Having genuine rapport with a child co-star is never easy, but Geisler pulled it off nicely, enough to elicit tear-jerking emotional connection with his audience when it counted.

- Mary Joy Apostol as Yumi Villanueva Janssen

- Yumi tells us that she came to know the truth about her dad a few years ago. Rustin had gone to rehab after returning to the Philippines but had relapsed after the death of his father. At one of his shows, he had suffered a stroke and had since been in a nursing home. Yumi tries to make him remember their time spent together, but Rustin seems to have no clue. Nevertheless, she spends the day with him and asks if she can continue to visit him. Rustin tells her that he doesn’t get any visitors and would be glad to see her more often. When she drops him off at his room, she finds that it is full of dollhouses that he has made. He talks about how he is making them for his best friend, who sings off-key. Turns out, Rustin remembers Yumi and the relationship he shared with her, but he doesn’t remember anything else, and that memory is what has kept him company all these years. Whatever we say about the movie, the ending is as beautiful and sweet as it could be, and it really warmed our hearts to see the smiles on their faces as the camera closed with a montage of their time together all those years back.

Recommendation

The whole story reads like a fairy tale, complete with fairy tale princess tropes and the frequent use of “explanation by fiat.” This should surprise no one, because the emo fairy tale is Francesca Lia Block’s signature move. In style, it’s actually too similar to Weetzie Bat. Because House of Dolls is intended for younger readers, the story is slightly less dark and definitely less sexualized than most of her work. But the bare-bones style (in keeping with classic FLB writing) doesn’t allow for a lot of plot or character development, and this is unfortunate because the subjects FLB addresses will be best understood by a slightly older crowd who might appreciate a bit more meat in their plot (say 6th to 8th graders, or even early high schoolers), but the text seems geared toward younger readers. I just can’t picture a reader knocking down something by Gail Carson Levine (also a fairy tale writer for this age group), and then really enjoying House of Dolls. It’s like expecting to be satisfied with a few Skittles for dinner when you’re used to a solid portion of mac’n’cheese.

It’s too bad, because House of Dolls isn’t a terrible story. It just feels like it was shoehorned into a format and marketing niche that it wasn’t originally intended for. The original hardcover list price was around $16 (which yes, I realize almost nobody pays). But for that kind of price, I’d want a full collection of stories, not just one. The book does feature illustrations by Barbara McClintock, which may distract from the sparseness of the plot.

House of Dolls by Francesca Lia Block

Published in 2010 by HarperCollins

Positives

The movie is set in a beautiful location. Hints of cultural diffusion (Filipino characters based in a European country) add a special knack that covers up for a draught storyline.

The theme of unawareness is put into the pedal fantastically through the characters of young Yumi and old Rustin. Both these characters never get to know of their relationship together as young Yumi is never exposed to her father’s true identity until she meets him years later when the latter tended to forget who Yumi was.

A series of flashbacks accounted for the smooth flow of the movie, keeping the audience engaged with Rustin’s character from time to time.

References[]

- New Exhibition Documents Forced Prostitution in Concentration Camps Spiegel Online, 15 January 2007

- Auschwitz, inside the Nazi state: Corruption, PBS. Accessed 28 April 2007.

- Memory of the Camps, Frontline, PBS

- Prose Works by Tadeusz Borowski (and others)

- Yudkin, Leon; various co-authors (1993). «Narrative Perspectives on Holocaust Literature». In Leon Yudkin, ed.. Hebrew Literature in the Wake of the Holocaust. Fairleigh Dickinson University Press. pp. 13–32. ISBN 0-8386-3499-0.

- Lentin, Ronit (2000). Israel and the Daughters of the Shoah: Reoccupying the Territories of Silence. Berghahn Books. pp. 33–34, 66 n. 4. ISBN 1-57181-775-1.

- ↑ Israel’s Unexpected Spinoff From a Holocaust Trial, Isabel Kershner, New York Times, September 6, 2007

You never know who’s watching…

‘Spine-chilling … makes you realise how little you ever know anyone!’ The Sun

‘A brilliantly creepy and insightfully written debut. I tore through it’ Gillian McAllister

‘Unnerving and spine-chilling’ Mel Sherratt

Corinne’s life might look perfect on the outside, but after three failed IVF attempts it’s her last chance to have a baby. And when she finds a tiny part of a doll house outside her flat, it feels as if it’s a sign.

But as more pieces begin to turn up, Corinne realises that they are far too familiar. Someone knows about the miniature rocking horse and the little doll with its red velvet dress. Someone has been inside her house…

How does the stranger know so much about her life? How long have they been watching? And what are they waiting for…?

A gripping debut psychological thriller with a twist you won’t see coming. Perfect for fans of I See You and The Widow.

Praise for The Doll House

‘A spine-chilling tale that makes you realise how little you ever know anyone!’ The Sun

‘A real page turner, I loved this story’ B A Paris, Sunday Times bestselling author of Behind Closed Doors and The Dilemma

‘Unnerving and spine-chilling in its sentiment’ Mel Sherratt, million-copy bestseller

‘Tense, suspenseful and unsettling… Phoebe Morgan is one to watch!’ Lisa Hall, bestselling author

‘A brilliantly creepy and insightfully written debut. I tore through it’ Gillian McAllister, bestselling author

‘Atmospheric, dark and haunting, I could not put this book down’ Caroline Mitchell, USA Today bestselling author

‘Deliciously creepy, genuinely unnerving and incredibly confident, The Doll House is the stellar first outing of a major new voice’ Catherine Ryan Howard, author of Distress Signals

‘Unsettling, insightful, evocative and poignant, Morgan’s writing is both delicate and devastating. will haunt the reader long after the pages are closed’ Helen Fields, author of Perfect Remains